by Lorraine Campbell

College Point, bordering the East River, a subway ride away from Manhattan, was a sleepy little hamlet existing in its own Twilight Zone. It was named for a long gone Lutheran college. Despite its industry, the town never lost its quaint residential charm.

Easily accessible to Manhattan by subway or car, by the 1950’s, the small north Queens town had a population of approximately 17,000, predominately German-American. Although many were first or second generation American, there was still much emphasis on ethnicity.

Historically, two hundred, twenty-six College Pointers took part in the Civil War. They were engineers and artillerists, and one was a musician in the Marine Band. The majority claimed Germany as their birthplace. Of those, 24 died in the service of their adopted homeland and 38 were wounded.

One of the town’s most famous visitors was Charles Lindberg who was a guest at the old Eskotter Hotel & Beergarden some months after being the first person to fly the Atlantic.

Large estates once bordered the town near beautiful Chisholm’s Park and the East River. The much loved, three-term NYC Mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia (referred to as “The Little Flower” because he stood five feet tall) summered in a lovely Victorian mansion facing the park, referred to in 1937 as "the summer city hall". He was a Republican who strongly supported FDR’s New Deal.

When I was a two-year-old towhead, the Mayor encountered us at the park swings. To mom’s delight, he picked me up, swung and danced me about. He really loved kids. Later, during a famous NY newspaper strike, he delighted in reading the adventures of “Dick Tracy” to us over the radio, and kept us current.

Occasionally, breezes carried acrid aromas from the tall factory smokestacks, as well as the shrill sounds of lunch and quitting time whistles. The large Lily Tulip Cup Company supplied the country with most of its disposable drinking cups.

A large sanitation incinerator near the town’s causeway entrance unfairly earned the town its nickname, “Garbage Point”, which irritated townspeople no end.

Despite becoming an industrial center, in the middle of the twentieth century, College Point retained an out-of-time quality, it‘s intrinsic, quaint charm undisturbed. A number of Victorian era buildings remained.

Despite becoming an industrial center, in the middle of the twentieth century, College Point retained an out-of-time quality, it‘s intrinsic, quaint charm undisturbed. A number of Victorian era buildings remained.Wild berries hung ripe for the picking in open fields. There were only a couple of apartment houses in town, mainly modest single or two-family homes, neatly hedged, with whitewashed foundations and swept walkways. Stately old maples and oaks lined the streets. Almost every house had a garden in the front, and one in the backyard.

For entertainment circa 1948, on Tuesday evenings, a few townspeople stood outside an appliance store window focused on small television screens for snowy glimpses of Milton Berle’s Texaco Theater. In the few saloons boasting a TV set, wrestling matches featuring Antonino Rocca or Gorgeous George were very popular. However, even in the saloons, wrestling was tuned out in favor of Archbishop Fulton Sheen’s weekly show.

College Point was known for its many bars, the main drag, 122nd Street, boasted a saloon on every corner, with another one tucked somewhere in the middle. Family involvement didn’t come easy to many College Point males. Various generations congregated in the many town bars for innocent companionship or escape.

No accounting of College Point is complete without mentioning Conrad Poppenhusen, a Germanic Horatio Alger, who did much for the town.

Charles Goodyear had just invented a process which hardened rubber, called vulcanization, and needed capital to turn his invention into profit. That’s where Poppenhusen stepped in. For several years, Goodyear granted him sole rights to vulcanization.

Poppenhusen came to the village of College Point in 1854, and not only built a factory, but a town. He opened the India Hard Rubber Comb Company, which eventually manufactured such diverse products as combs, brushes, buttons, corset stays, thimbles, funnels, flasks, inkstands, photographic goods, surgical supplies and dollheads. College Point became known as the “rubber capital of the Northeast”.

The town also housed many German breweries.

Well-shaded beergardens and amusement parks made it very popular for day trips, steamboat excursions, and political clambakes. The Village Grove’s grounds were so large, it could host as many as four organizations simultaneously.

The town's silk mill supplied silk ribbon, much in demand by the yard for girls’ hair adornments and hat bands.

The town also housed many German breweries.

Well-shaded beergardens and amusement parks made it very popular for day trips, steamboat excursions, and political clambakes. The Village Grove’s grounds were so large, it could host as many as four organizations simultaneously.

The town's silk mill supplied silk ribbon, much in demand by the yard for girls’ hair adornments and hat bands.

Poppenhusen’s employees were newly arrived Europeans, mostly German and later Irish. He recruited immigrants as they stepped off the ship at Manhattan piers.

During the Civil War, the company flourished with orders for flasks, cups and uniform buttons.

On his fiftieth birthday in 1868, as a gift of appreciation to the town, Mr. Poppenhusen donated $100,000 to construct the Poppenhusen Institute, a stately five-story Victorian edifice with sloping mansard roof and tall arched windows.

He followed that with another $100,000 donation for teachers’ salaries and operating costs.The institute was run by the “Conrad Poppenhusen Association”, incorporated for:

“The protection, care and custody of infants; the advancement of science and art, with such equipment as may be useful for that purpose; and the improvement of the moral and social conditions of the people.”

The institute was College Point!

Town meetings were held in the grand ballroom, which doubled as the Village Hall. At one time Mr. Poppenhusen was justice of the peace and president of the village trustees.It was the first home of the Congregational Church, the public library, the firehouse, the College Point Bank, even the jail, with two cells in the basement.

Town meetings were held in the grand ballroom, which doubled as the Village Hall. At one time Mr. Poppenhusen was justice of the peace and president of the village trustees.It was the first home of the Congregational Church, the public library, the firehouse, the College Point Bank, even the jail, with two cells in the basement. In 1870, it housed the first free kindergarten in the country. German teachers were imported for the growing kindergarten.At Poppenhusen Institute, workers and their families studied English, learned a trade, and were introduced to art, music, theater, literature and history.

Thirty-five years after the institute was built, my grandparents learned English there.

It was there that my maternal grandfather, Johann Mayer, studied the art of fresco painting; later painting frescoes in area churches. It was there that my mother learned bookkeeping.

Additionally, paternalistic Conrad Poppenhusen provided homes for employees, cobblestoned roads, drained the marshes, started a railroad and brought clean running water and a sewage system to the community.

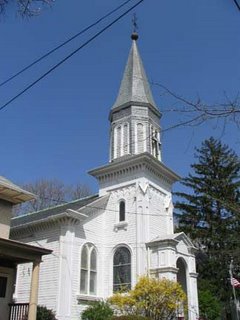

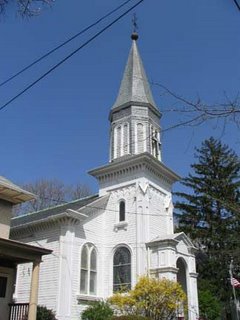

Mr. Poppenhusen also donated an additional $30,000 to build the First Reformed Church in 1873.

It was built in the small town New England style, adorned with a bell tower and gingerbread trim.

It was built in the small town New England style, adorned with a bell tower and gingerbread trim.

It was built in the small town New England style, adorned with a bell tower and gingerbread trim.

It was built in the small town New England style, adorned with a bell tower and gingerbread trim.He so loved his adopted country, in 1876, he took all his employees and their families (over 1,000 individuals) by special trains to the nation’s centennial celebration in Philadelphia.

He was a “cradle to grave” employer, organizing a mutual benefit association to assure sick benefits and death benefits, an unheard of practice at the time.His beneficence endeared him to his workers, numbering 1,500 at one time.Although a contemporary of the ruthless Robber Barons, he became known as, “The Benevolent Tycoon”.

Sadly, the great benefactor fell on hard times, following the reckless business acumen of his three sons, who plunged into buying railroads. A combination of a hodge-podge of stations, rolling stock and tracks, plus the recession of the 1870’s drove him into bankruptcy and his fortune was lost. He tried to recoup, both in Germany and College Point, but was unsuccessful.He died in College Point in 1883, and his mansion was demolished in 1905.

Later, during Prohibition the town's resorts declined, ending an era.

During the 1970’s, the Poppenhusen Institute itself had fallen on hard times, and came within a razor’s edge of being demolished in 1980. College Point residents formed "The Concerned Citizens for the Poppenhusen Institute", and after an expensive, three-year court battle worthy of Poppenhusen himself, won the right to continue to exist. It’s primarily funded by city and state grants and is still a community cultural center.

One hundred and thirty-six years after it was built, today’s children visit the institute to learn music, dance and karate. They can also view a fire department exhibit with an original hose wagon and replica of a firehouse.

Fittingly, the institute also houses a Native American Museum, which focuses on much earlier residents of that area, the Matinecock Indians of College Point.

During Poppenhusen’s era, braumeisters all around New York City were opening breweries, such as Ehrets, Piel’s, Rupperts, F&M Schaefer, and Liebman, which later produced Bock and Rheingold.By then the town had also become a fashionable summer resort, with a ferry connection to Clason’s Point, then the “Coney Island of the Bronx”.

Not surprisingly, College Point soon boasted many German biergartens, such as The Hofbrau, Muchler’s, Eiffel’s, Rousche’s Tavern, The Cozy Corner, The Village Grove, and most notably, Witzel’s, later known as Flessel’s.

Witzel’s Resort was built in 1872, during President Grant’s administration. It predated the Brooklyn Bridge. Along with Poppenhusen’s Institute, Witzel’s was the heart of the community. It was a hotel, bar and restaurant, and many College Point weddings were held there. Horses were once tethered at its wooden porch. Patrons sat at the solid onyx bar rail, polished to a luster by more than a century of tipplers’ hands. Diners relished their wiener schnitzel, sauerbraten and goulash.

Only its name changed when it became known as Flessel’s. Occasionally, the beveled glass behind the bar reflected my father’s image, both as fill-in barkeep and customer. Marty liked an occasional ale himself, and sometimes a few more.

Later, during the 1950’s, I’d sometimes enjoy Flessel’s wienna schnitzel for lunch, while working at a nearby EDO Corporation, a well-known electronics manufacturer. I remember the day, the famed French underwater explorer, Jacques Costeau, toured EDO, together with some of his crew of the 141 foot long research vessel, the Calypso.

By 1998, Flessel’s had served its last Dinkel Aker.

Old-timers and town historians were very saddened when the 127-year-old structure succumbed to a wrecking ball and bulldozers in 1999. It was the last of the town’s summer resorts and beergardens.

The beerhalls all had solid wood floors, with plenty of room to polka or waltz to Johann Strauss, play billiards or even bowl. They all featured a separate, discrete side “ladies’ entrance”. There were also outdoor areas for dining, dancing, and horseshoes. Weekends were mini Oktoberfests, with entire families taking part in festivities. They loved to sing, as well as dance. Beautiful, strong voices would join in:

“Du du liegst mir am herzen

(You are in my heart always)

Du, du liegst mir im sinn

Du, Du machst mir viel schmerzen

Weibt nicht wie gut ich dir bin

Ja, ja, ja, ja

Weibt nicht wie gut ich dir bin.”

Sometimes it would get a bit rowdy when the Irish showed up, but for the most part, it was great fun for the entire family.

Irish and Italians also became barkeepers, creating a town of many taverns.McCoy’s, The Point Tavern, The Friendly Tavern, The Knickerbocher, Behan’s on the water, The Midway, The Tin Shed, Eldorado, Miraglia’s, etc., won College Point the dubious distinction of the most drinking establishments in a small town. Occasionally, before Sunday dinner, my dad would “rush the can”, he’d grab a small stainless steel pot by the handle and have it filled at the corner tavern with beer on tap. I was allowed a half glass on Sundays.

My aunt Ann and uncle Joe owned a tavern in town, Miraglia’s, and she made book there. When their son, my cousin Joseph, had the distinction of being the youngest CPA in NYC, he came by his accounting skills honestly.

We lived in an area of town the locals called Grantville, in a lovely corner home landscaped with a huge blue spruce tree and azaleas. My maternal grandparents, Elizabeth and Johann, ethnic Germans, arrived at Ellis Island from Austria-Hungary’s Banat in 1904, and bought their house after decades of hard work and sacrifice raising four children. It was one of the first homes in our area wired for electricity.

Beyond the entry foyer, French doors opened to the living room. A swinging door separated the dining room from the white tiled kitchen. Upstairs were three bedrooms and one bathroom. Originally, Grandma used the basement as a root cellar. During the 1930’s, the basement was remodeled into an apartment. From my bedroom, I could see the 1939 NY World's Fair in the distance.

Beyond the entry foyer, French doors opened to the living room. A swinging door separated the dining room from the white tiled kitchen. Upstairs were three bedrooms and one bathroom. Originally, Grandma used the basement as a root cellar. During the 1930’s, the basement was remodeled into an apartment. From my bedroom, I could see the 1939 NY World's Fair in the distance.

Grandma Elizabeth took great pride in her roses, hydrangeas, lilacs, lily of the valley, vegetable garden, fruit trees, and berries. I can still see tomatoes lined up in various stages of ripening. I can still taste her apple strudel, fresh peach upside down cake, and jelly donuts. When Grandpa Johann (who Grandma called Hans) was still alive, they’d ferment wine from their own grapes. A large, gray metal watering can was used when the heavy black rubber hose couldn’t reach. She was very frugal with the water, never wasting a drop.Grandma attributed her magnificent roses and beefsteak tomatoes to buried fishheads. Sometimes the fruit peddler’s horse would contribute very fresh fertilizer. Often one rose harbored many Japanese beetles, clustered together. My job was to pick them off. I’d then sentence them to death in jars of water and tobacco.

My grandparents lost their second born, Frank, during the worldwide influenza epidemic of 1918. Two years earlier, their daughter, Teresa, (my mother) had contracted infantile paralysis.

After Grandpa’s death, Grandma became a businesswoman in the 1920’s, with a stationery store. Crime ring members threatened her, saying if she didn’t pay them protection money, they’d break her plate glass windows. Grandma’s temper got the best of her. She picked up a broom, yelled “Gut en Himmel!” and chased them out of the store. They never bothered her again.

As a young man, Uncle Adam trapped muskrats in the local wetlands we called the meadows. Eventually three relatives sported full-length Muskrat fur coats. They looked great, poor man’s mink!

A chum of Uncle Adam, Appolonius Baumgartner, often went trapping with him. Later, he joined the priesthood and eventually became Archbishop of Guam.

A chum of Uncle Adam, Appolonius Baumgartner, often went trapping with him. Later, he joined the priesthood and eventually became Archbishop of Guam.

There were only three doctors in town, all general practitioners. The most loved was Dr. Martin Jurkowitz, who everyone called, “Jurky”. He practiced from his home, now reminiscent of Dr. Welby’s TV home, picture perfect and next to the Poppenhusen Library, not far from Poppenhusen Monument.Norman Rockwell might have been inspired by Doc Jurkowitz’ waiting room, crowded with patients of all ages and conditions.

Although the good doctor prescribed iodine treatments for my Mom’s thyroid, he was famous for his pink pills, which he gave out freely as a cure-all for everything from headache to an ingrown toenail. He used his fluoroscope freely, which delighted young onlookers. He also did a great Donald Duck imitation to set kids at ease.

Lined up outside the A&P and Bohacks supermarkets, babies were left tethered in their carriages while their mothers shopped. None of the women drove, and some used baby carriages just for hauling groceries before the advent of collapsible shopping carts.

“The College Theater”, the local movie house, was better known as “The Itch”. To avoid ear pulling and banishment, town kids learned not to mess with the sturdy matron who monitored the Saturday matinees. Wednesday was Bingo Night. Other nights, dishes were raffled. Double features were the norm. Between films, the Red Cross sometimes solicited funds with collection baskets sent into every aisle.

After the movies, we’d stop at The Sweet Shop, Schweers, or Jehrs’ (pronounced Jeers) for an ice cream soda or banana split. As a kid, I always wondered about Johnny Jehrs eyesight as he worked behind the fountain. He insisted on calling me, “Dimples” although I never had any.

When we weren’t bike riding or skating in the streets, the town kids played stickball, stoopball or catch with our “spauldeens” (pink rubber balls manufactured by Spaulding), potsy, ringalerio, tag or “hango seek” (hide and seek) until the street lights came on. We learned to ice skate in the frozen marshlands, forming “whips”. Summers, the marshlands provided pungent “punks” (cattails), which we’d light to keep mosquitoes away.

There were also four leaf clovers to be found, as well as frogs and fireflies to be caught. At bedtime, I tried reading in the dark, using a jar of fireflies, or listening to the radio via the crystal set my Uncle Ralph made for me.

One night after supper, Ronnie Brodeur, the boy next door, and I decided to go frog hunting in the huge sandpits. I was seven, and we managed to sneak out of my house together. It was dark by the time we got back home. Our parents had called the police, and we were both punished. We couldn’t understand all the fuss over a little innocent frog hunting.

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, when Pearl Harbor was attacked I was seven. The next day, as I walked to school, I remember being frightened by the sight and sound of overhead airplanes. College Point was in LaGuardia Airport’s flight path.

The War Effort took priority over everything. We bought War Bonds and Stamps. My father contributed regularly to the Blood Drive. Backyards were transformed into victory gardens since rationing became a way of life. Many homes proudly displayed small window banners bearing one blue star for every serviceman in the family. A gold star signified a death.

A few months after Jim Burns graduated from P.S. 29 as class valedictorian, V-J Day heralded the end of World War II in August 1945. My cousins and I celebrated outdoors by banging on our moms’ Wearever pots and pans.

When I was twelve, I once again caught hell from my parents for riding “Blue Beauty”, my second-hand Schwinn over five miles to LaGuardia Airport, via then 4-lane, busy Grand Central Parkway. My close friend, Gertie Hermann, and I just wanted to watch the planes take off and land.

I spent a lot of free time at the Hermann apartment. Although their mother was bedbound, she always had a big smile and pleasant word. Her husband had passed away years earlier. The six children took turns caring for her. Their apartment, over a store, was full of activity, laughter and love. At least one of the four girls could usually be found ironing in her slip, the ironing board permanently set up in the kitchen, and the iron plugged into a ceiling fixture.

I always got a kick out of Romeo Hermann, who was a dapper dresser and considered himself a ladies man.

Gertie’s older sister , Ida, worked next-door in Damoisey’s Luncheonette & Stationery store, and served me cherry cokes, free of charge. Damoisey’s store was supposedly off-limits for me. Seems my father’s Dad (who died before I was born) was living in sin with old Mrs. Damoisey.

Mrs. Damoisey was a town oddity. She was not only a business woman, but wore dark red lipstick extended well over her natural lip line, and had the longest, reddest fingernails I had ever seen. I had the impression she didn’t particularly like anyone who wasn’t as old as she, and figured she had to be at least 100!

Although estranged from Grandma and living with Mrs. Damoisey, every Sunday afternoon, Grandpa would show up at Grandma’s to play pinochle.That was after Grandma finished cooking and baking for the priests of St. Fidelis.

Local churches played a large part in town life. Church bazaars were frequent. Homemade strudel, stollen and wurst would be raffled, along with fine crocheted doilies and other handiwork. The ladies of the St. Fidelis Rosary Society and the Altar Society would cajole red-faced Father Reichert into waltzes and polkas, after he was well fortified with a few cold, sudsy Rheingolds.

My father, Marty, had been an altar boy. Nevertheless, he became disenchanted with the church immediately after taking his wedding vows in 1931. He was only 20 years old, and due to the Depression, down on his luck.He gave the priest a small gratuity for performing the marriage ceremony. Dad never forgot the priest's thank you: "You can't get blood out of a stone!"After that, he avoided going to church. Relatives long prophesized, “If Marty ever enters the church, the ceiling will fall in!”Nine years later, in 1941, I was seven, standing in line to make my First Holy Communion, worrying about the roof of the church falling on everyone.